Private fund managers have split into two tiers, and most funds don’t yet realize which one they’re in.

At one tier, CFOs model the full economic impact of a proposed anchor LP’s fee terms across 40 existing investors in 20 minutes. They run five fund structure scenarios in an afternoon. LP-specific reports generate automatically at quarter close. They say yes to bespoke side letter terms because systems can track the obligations.

At the other tier, CFOs spend a week on spreadsheet archaeology to understand a single MFN (Most Favored Nation) trigger. Complex LP requests get turned down because the back office can’t handle them. Side letter conflicts surface two years after creation. Capital goes to competitors who can move faster.

The difference is agentic AI.

This isn’t another technology trend to monitor; it’s already here, and the gap between those who embrace it and those who fall behind is expanding. The funds that moved early have already changed what LPs expect. Institutional investors who receive proactive updates triggered by material events, who get answers to diligence questions in hours, who see modeling on proposed terms before the first negotiation call—they notice when the next fund they evaluate can’t do any of this. LP expectations don’t reset downward.

The constraint that defined fund operations for decades—that complexity requires headcount—no longer applies to top funds. Agentic AI has become a prerequisite for remaining competitive.

In this piece, we’ll take agentic AI from buzzword to execution plan—starting with the data foundation required to make any of this work, and then showing what becomes operationally possible.

The Data Foundation: Why It Comes First

The sophistication afforded by AI doesn’t matter if the underlying data is wrong. An agent that can execute a multi-step capital call workflow isn’t helpful if it’s drawing from incomplete transaction records or misinterpreting ambiguous side letter language.

Any serious implementation starts with the data layer, with the goal of transforming fragmented data sources into a structured model that mirrors how your fund actually works.

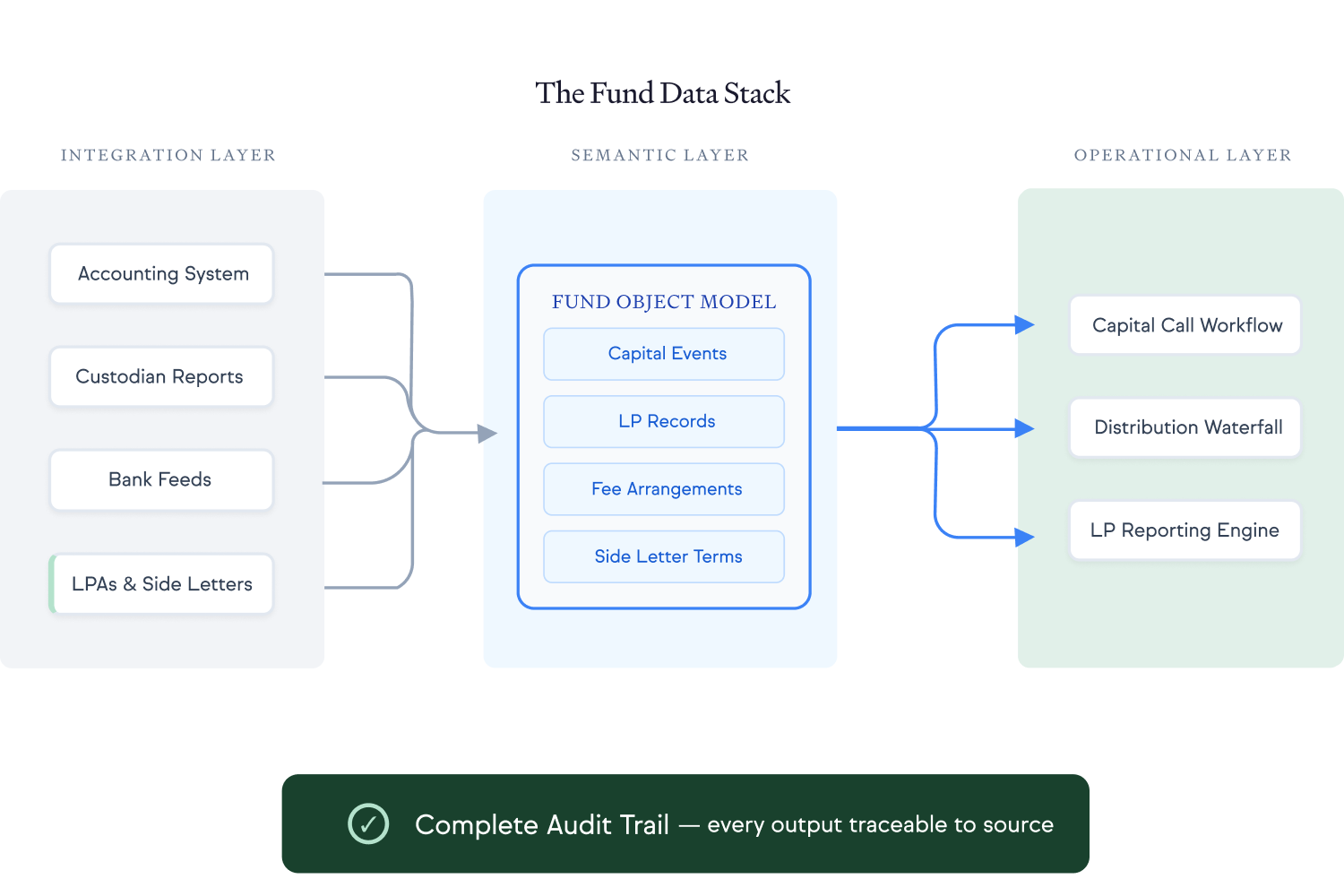

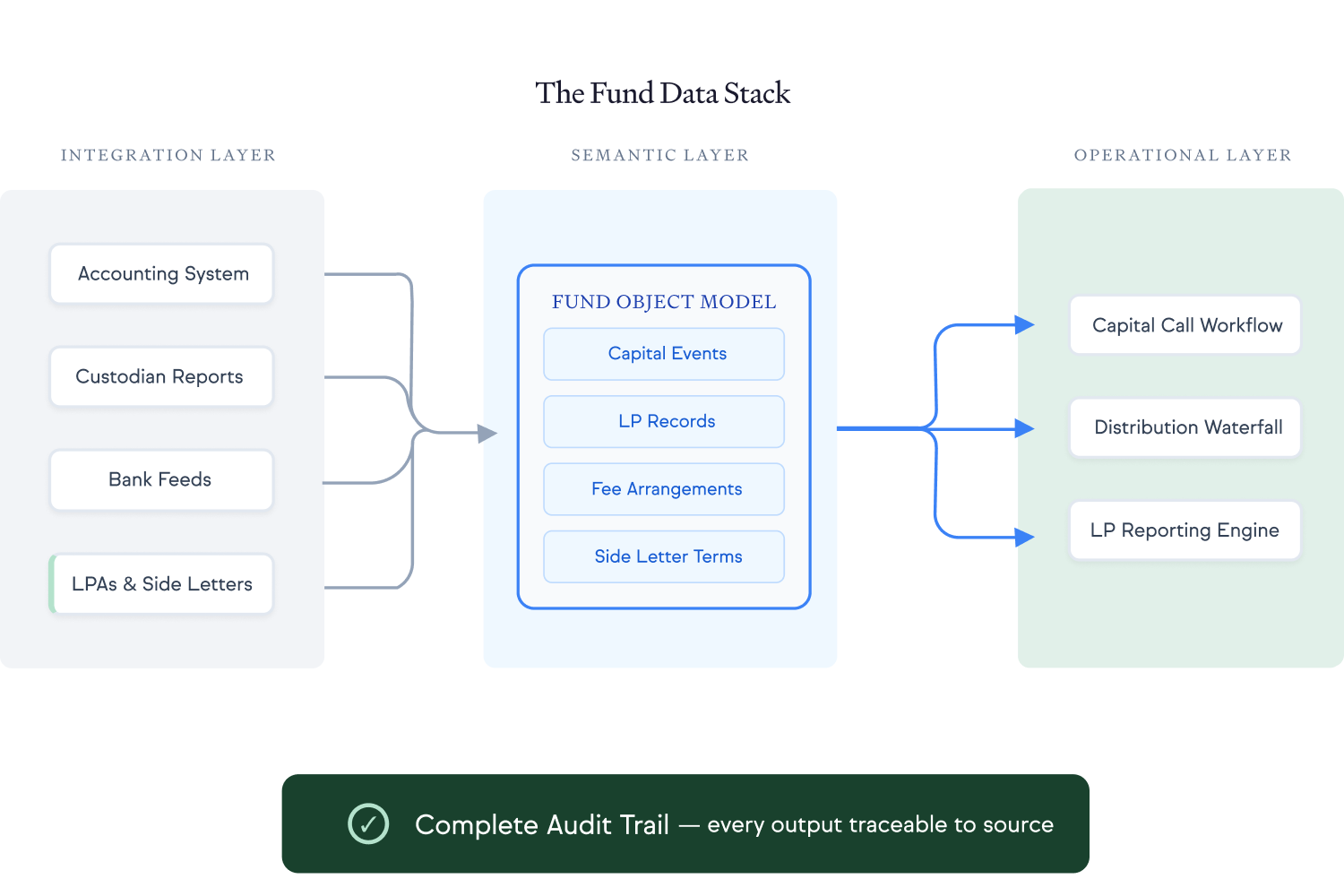

The stack has three components that work together:

The Integration Layer pulls data from source systems—accounting platforms, custodians, bank feeds, document repositories—and normalizes it into a consistent format. Most funds have transaction data scattered across disparate systems, with legacy records in formats that don’t map cleanly to current structures. The integration layer handles the translation, so AI agents can query any data point regardless of where it originated.

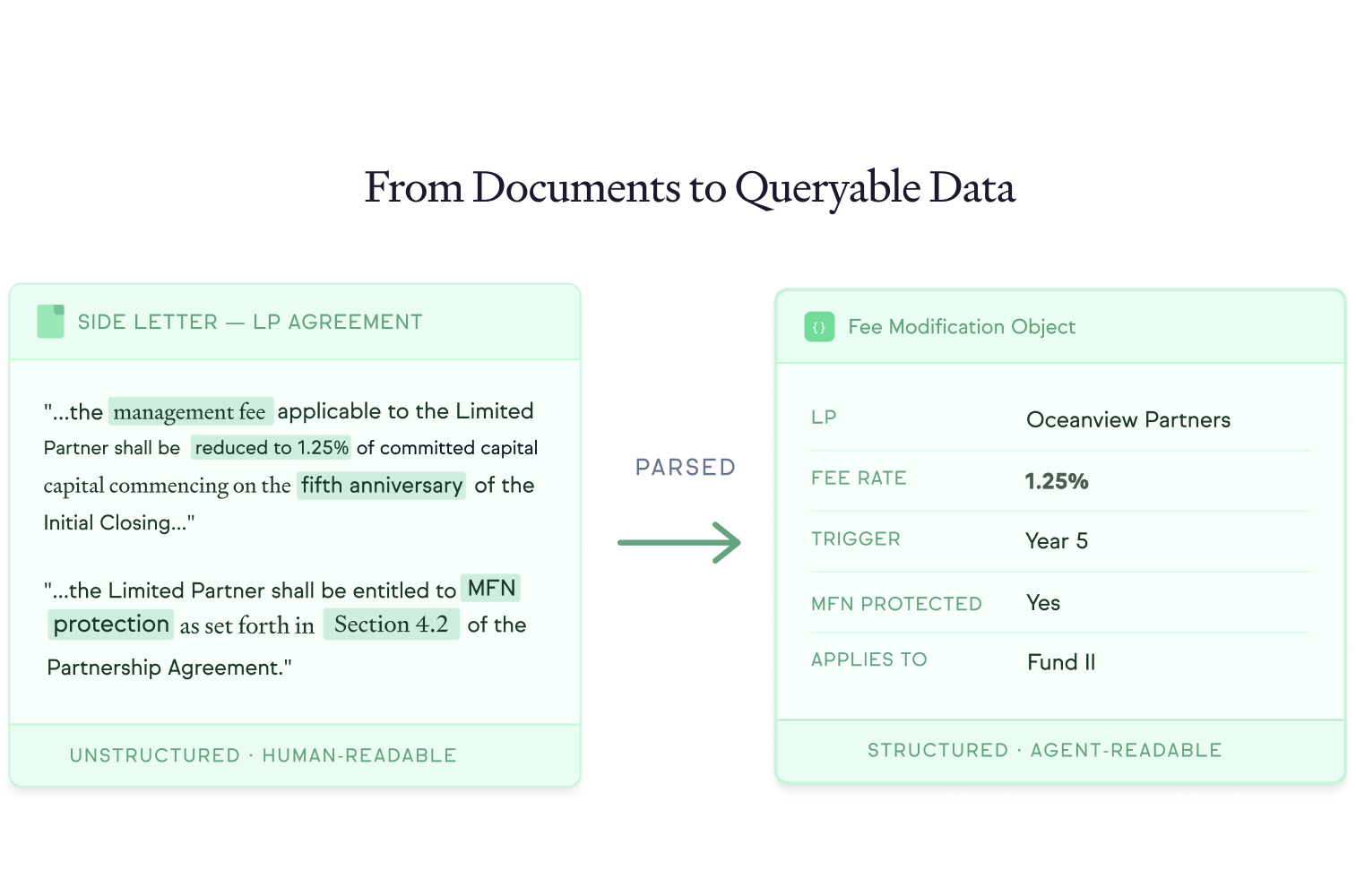

The Semantic Layer turns raw data into meaningful business objects. For example, transaction records are mapped to Capital Events, PDF clauses become structured Fee Arrangements with defined parameters, and side letter provisions are converted into queryable Obligation Records with trigger conditions and compliance status. The governing documents are parsed into queryable data structures. This is where agents—AI systems that can autonomously execute multi-step tasks, make decisions based on context, and take action without constant human direction—apply the correct logic to each LP and each transaction. Unlike a chatbot that simply answers questions, an agent reads your data, determines what needs to happen, and does the work.

The Operational Layer defines what actions can be taken and what rules apply. Each capital call workflow, distribution waterfall, and reporting obligation is modeled as a process that connects to underlying business objects. Now AI agents can reason about your fund and perform operational actions—like issuing capital calls or generating statements.

Critically, this layer also logs every action the agent takes: what data it read, what logic it applied, what outputs it generated, who approved it. This makes the system auditable. CFOs evaluating these tools have one core question: can I trust the output? The data foundation makes every output traceable to source documents and every calculation reproducible.

The funds building this layer now compound their lead with every capital event. The funds that delay will be building it later anyway—under more pressure, with less time, while competitors pull further ahead.

A New Baseline for Operational Efficiency

Funds using agentic AI process capital calls in minutes that used to take days. They reconcile transactions across multiple systems automatically. They generate LP-specific reports at quarter close without analyst time. The work is high-stakes and unforgiving—a single error in an allocation can cascade across funds, requiring restatements and difficult conversations with LPs—but the speed and accuracy of agent-driven workflows have made manual approaches obsolete.

These funds have an AI assistant that has parsed every LPA term, side letter provision, and waterfall mechanic for every fund—and has codified them into machine-readable logic that the system can execute. An assistant that performs complex calculations at extremely high speed and accuracy, and that will never forget a most-favored-nation clause or miscalculate a catch-up provision.

These capabilities are no longer differentiators. They’re becoming the baseline:

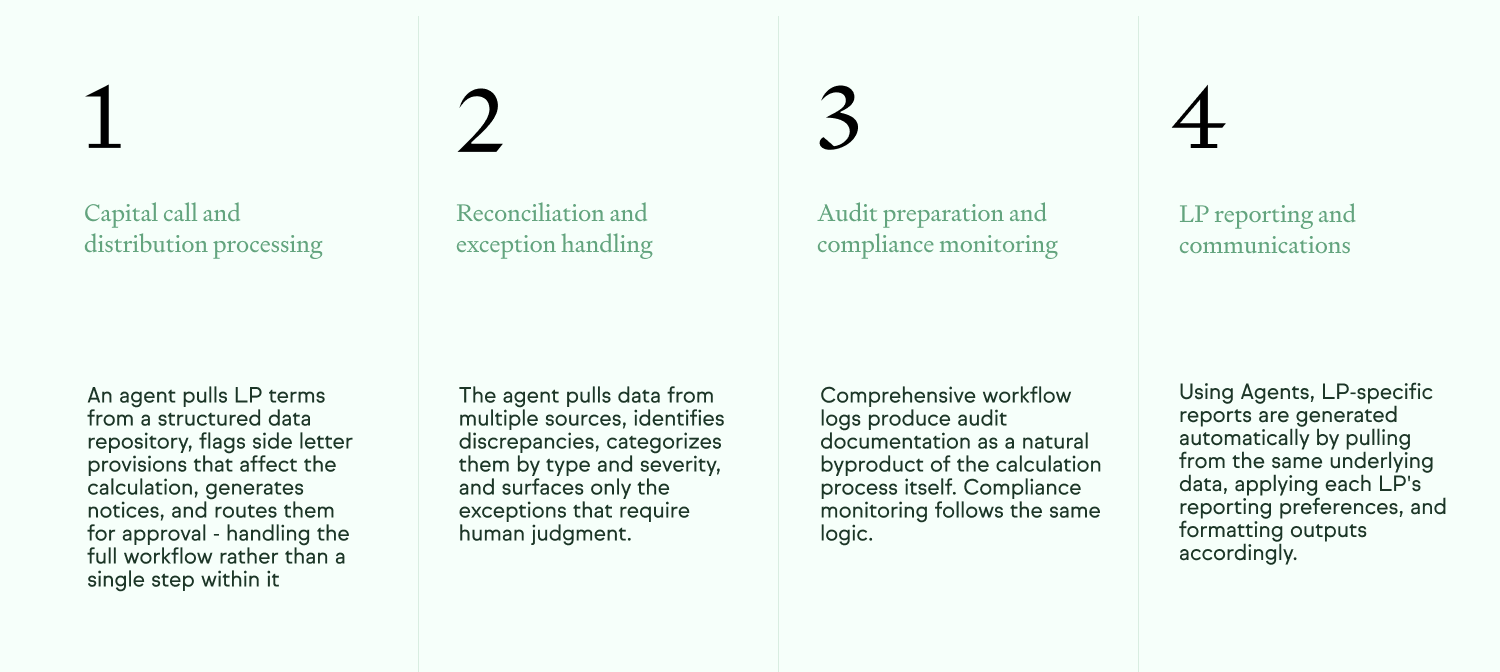

- Capital call and distribution processing. The workflow for a capital call involves determining the amount to be called, calculating each LP’s share based on commitment percentages and side letter modifications, generating notices with correct wire instructions, and tracking receipt through reconciliation. At a fund with negotiated terms across dozens of LPs, this consumes days of staff time—at funds still doing it manually. The agent pulls LP terms from a structured data repository, flags side letter provisions that affect the calculation, generates notices, and routes them for approval—handling the full workflow rather than a single step within it. Distribution waterfalls work the same way: the agent traces capital through multiple return thresholds, applies LP-specific carry rates, and executes catch-up provisions. This reduces days of work to minutes and produces a complete audit trail—which means your team closes faster, LPs receive funds sooner, and you have documentation ready if questions arise months later.

- Reconciliation and exception handling. Fund administrators at most shops still spend hours each week reconciling bank statements, custodian reports, and internal records. The agent pulls data from multiple sources, identifies discrepancies, categorizes them by type and severity, and surfaces only the exceptions that require human judgment. The administrator’s role shifts from routine manual matching to exception review. The time savings compound weekly—freeing capacity to support additional funds or investor requests without adding headcount.

- Audit preparation and compliance monitoring. Audit cycles consume CFO attention for weeks. Each requires assembling documentation, responding to requests, and reconstructing the logic behind historical calculations. With comprehensive workflow logs, audit documentation is a natural byproduct of the calculation process itself. Compliance monitoring follows the same logic—rather than manually tracking deadlines for investor communications and side letter obligations, the system monitors approaching deadlines and flags issues before they become problems. CFOs at these funds spend the audit season on strategy. CFOs at other funds spend it on document retrieval and inevitably fall behind the competition.

- LP reporting and communications. Institutional LPs increasingly expect more granular reporting, following ILPA-compliant formats and including segmented performance data. Producing bespoke reports for multiple LPs is time-intensive if done manually. The agent generates LP-specific reports automatically by pulling from the same underlying data, applying each LP’s reporting preferences, and formatting outputs accordingly. What used to require a dedicated analyst becomes an automated workflow triggered by the close of each reporting period. The analyst now works on strengthening investor relations (or works at a competitor who gave them better tools).

The CFO as Chief Financial Orchestrator

Agentic AI gives the CFO the ability to think ahead. With a strong data foundation, CFOs model the downstream effects of a proposed fund structure before committing to it. They run scenarios across the portfolio in minutes. They spot patterns in LP inquiries that flag issues or opportunities before they surface. The CFO role shifts from reporting on last quarter’s performance to shaping next quarter’s decisions, orchestrating AI agents to produce the necessary inputs.

This is a category of analysis that manual processes cannot replicate at any staffing level.

- Fund structure design. A new vehicle—whether a continuation fund, co-invest, or GP commitment entity—is typically structured based on precedent and intuition. An agent models these decisions against existing fund data: how different fee arrangements affect economics across LPs, where a proposed structure conflicts with existing side letters, and which terms trigger MFN provisions elsewhere. The CFO sees tradeoffs before committing to a structure. Without this capability, you’re making structural decisions with incomplete information—and you won’t know what you missed until it costs you.

- Scenario planning. It used to take days or weeks to pull data from multiple systems and build a one-off model to answer a single question (e.g., what happens if we call capital early, if a portfolio company exits at a lower multiple). So this type of analysis only happened for major decisions. An agent runs these scenarios on demand, pulling live data and applying current terms. Five structures tested in an afternoon versus one analysis commissioned per quarter. The fund that can model faster makes better decisions. The fund that can’t is flying partially blind.

- Proactive investor updates. LP information requests have exploded in volume and complexity. The old cadence—quarterly reports and annual meetings—doesn’t match what institutional investors now expect. They want transparency on material changes as they happen: a significant exit, a markdown, a shift in portfolio composition. An agent monitoring portfolio data detects these triggers, drafts communications tailored to each LP’s reporting preferences, and routes them for review. The IR team stops reacting to requests and starts anticipating them. LPs notice the difference—and they remember it when evaluating your next fund.

- Continuous monitoring. A CFO managing multiple funds can now watch every variable in real-time. The agent tracks which LPs are approaching commitment limits, which funds are nearing the end of their investment periods, where recycling provisions are underutilized. It flags items requiring action and recommends next steps—noting that an LP’s re-up probability has dropped based on communication patterns, or that a rebalancing opportunity exists given current allocations. The CFO reviews and decides; the agent ensures nothing falls through the cracks. At funds without continuous monitoring, problems surface only after they’ve metastasized.

The Separation Is Already Visible

The operational gap between top-tier funds is clear to see. Fundraising timelines have compressed—LPs at leading funds get answers in hours instead of weeks. Fund economics improve when structure decisions are modeled against comprehensive data rather than precedent and intuition. LP experience has shifted as investors receiving proactive updates triggered by material changes, tailored to their preferences, carry different expectations to every fund they evaluate afterward.

Consider what this looks like in practice. A pension fund is negotiating to anchor your new fund at a 1.5% management fee with an MFN clause. Understanding the true cost used to mean a week of spreadsheet archaeology—pulling every side letter, mapping MFN triggers, calculating fee impact across 40 LPs. Most CFOs ran a rough estimate and hoped for the best.

With an agent, this is modeled in 20 minutes. It surfaces that six other LPs have MFN rights triggered by management fee reductions. The proposed “anchor discount” would become a seven-figure annual fee haircut across the fund. Armed with this intelligence, you shift strategy—offering the pension fund a co-invest allocation instead, which doesn’t trigger MFN. (The CFO without this capability accepts the terms, discovers the true cost months later, and has a difficult conversation with the GP about the fee impact no one modeled. The average fund still operates this way).

The same intelligence compounds across fund vintages. When designing Fund IV’s co-investment vehicle, the agent pulls every co-invest side letter from Fund III and maps the constraints that were unknowingly created: three LPs with overlapping “first look” notification windows that conflict, allocation formulas pegged to incompatible metrics, and an MFN clause that technically extends to co-invest economics though it’s never been applied. The team has been working around these manually for two years. Now they see them clearly before replicating the same friction into Fund IV—and can restructure the terms to eliminate conflicts before they create problems.

Funds without this visibility are copying their own mistakes into their next vehicle. They won’t know until they’re managing the same workarounds for another two years.

Complexity has flipped from a cost to an advantage—but only for funds with the infrastructure to manage it. The LP who wants a custom fee arrangement, the sovereign fund that requires a specific reporting format, the family office that needs co-invest allocation rights with particular notification windows—leading funds say yes to all of it. The system tracks the obligations, calculates the implications, and flags conflicts for resolution.

Funds still running manual processes are turning away LP requests that competitors are accepting. They’re losing allocations to funds that can offer more flexibility. They’re spending senior time on operational catch-up instead of investor relationships and deal flow.

Conclusion

The CFO role has moved to the forefront of how funds compete. The complexity that now defines private fund management—multiple vehicles, negotiated terms, bespoke LP arrangements—makes operational capabilities a strategic necessity, not a back-office concern.

Agentic AI is what separates the funds that can capitalize on this complexity from funds that are constrained by it. It handles the heavy lifting that legacy systems cannot and surfaces the insights that manual processes cannot produce. The CFO can then focus on the strategic decisions that drive fund performance.

The separation between the two tiers of private fund managers is accelerating, and the funds that deploy agentic AI are the ones that will win. The only question regarding agentic AI adoption is timing—now, while the gap is closeable, or later, when the distance is greater and the pressure is higher.

Recommended Content